HeLa Cells

Have you ever wondered how the world got to know about cervical cancer? How we have a cure?

Have you ever wondered how scientists and researchers have made waves in medicine and pharmaceuticals?

As much as modern resources like to attribute success to professional healthcare, this black woman was the first one to discover what cervical cancer would look like.

A Story Lost In Time

In 1951, a young mother of five entered the John Hopkins’s Hospital’s black wing, complaining of vaginal bleeding. She had self-examined herself by inserting her fingers up her vaginal canal, and felt an unnatural mass.

Upon examination, she was asked to get a biopsy. This was when one of the biggest thefts in the world of medical practice occurred.

A sample of her cells was to be taken for biopsy, but without her knowing, more samples were taken. No consent, nothing. Her cells were sent to the lab of Dr. & Dr. Gey, who were trying to manufacture a line of immortalized cells by using umbilical cord fluid.

They lucked out.

Henrietta Lacks’s cells were the first ever line of immortalized cells. Named as the HeLa cells, these cells are used in every lab over the world to test viable cancer treatments, drugs and more.

A few months later, in October 1951, Lacks passed away.

HeLa Cells Today

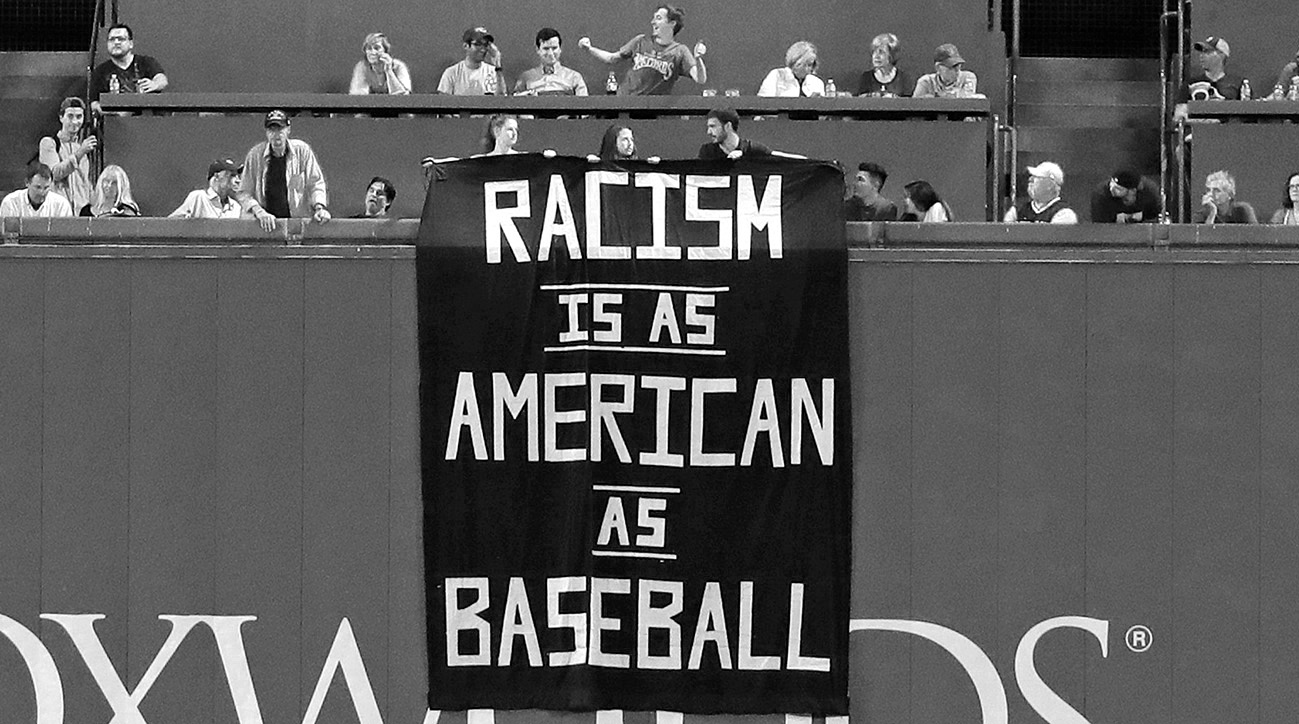

The story of Henrietta Lacks sparked heated debates about bioethics, medical practices and consent all over the world. It also highlighted the plight of black people in the 1950’s, and how their bodies were dehumanized as commodities.

Lacks was a poor tobacco farmer with African American roots and one of the healthiest sturdiest biochemistries; she was a picture of health, and a glaring example of injustices committed against blacks which Medical Anthropology, Cultural History and Human Sciences all debate about to date. Science and research have held the belief that the end justifies the means – but does it, really?

While the world of medicine and science has made progress and profit today, Lacks’s family still lives in impoverished conditions, struggling to make ends meet despite the legacy of the HeLa cells. The decades’ long injustice of Henrietta Lacks is a constant reminder of the dark history of the world, and is a black mark in the history of medical science.

Her story begets the questions:

If it was a white individual, would the circumstances have been different?

If it was a white woman, would she have been wronged like this?

Has anything changed?