Paper Queens

(Source Ramdasha Bikceem's zine "GUNK" issue number 4)

Radical Women Of Color Are Keeping Zine Culture Alive

At the height of the Riot Grrrl punk movement in the early 1990s, something monumental occurred. Young women, frustrated with patriarchy, grabbed paper, pens, glue sticks, and scissors, and passionately took to the task of creating their own zines. Zine culture spread like wild-fire as young women utilized underground punk spaces to make their militant voices heard. For young white women who felt ostracized by sexism in punk, it was a liberating time. However, despite the zine explosion, there was a group whose political, social and cultural experiences were even further marginalized; women of color who contributed to the zine movement were routinely erased.

“Riot Grrrl and its attendant zinesters was still a young version of a ladies’ lunch society—except that the ladies have blue hair and weird clothes,” recalls Jennifer Bleyer, an original member of Riot Grrrl in the early ‘90s in Cut-And-Paste Revolution. “Participating in girl zine culture requires that one have the leisure time to create zines, access to copy machines, and other equipment, money for stamps and supplies, and enough self-esteem and encouragement to believe that one’s thoughts are worth putting down for public consumption.”

Riot Grrl zines | Source: ItsNiceThat

Zines such as Bamboo Girl and HUES (Hear Us Emerging Sisters) were circulated in punk scenes as an answer to their voices being overlooked. Bamboo Girl, created by Sabrina Margarita Alcantra-Tran, focused on the intersections of gender, class, race, and queerness in regards to Asian-American and mixed-Asian women in underground subcultures. She remembers her impulse to create a zine in The Herstory of Bamboo Girl after being unable to find material that addressed her struggles. “I was sick of explaining my heritages when fielding the constant, ‘Where are you from?’ or ‘What are you?’ questions, and I was experiencing way too much harassment on the streets of New York City, which took the form of catcalls based on racial stereotypes. I didn’t have a constructive way of expressing my annoyance, anger, and rage, and it surely didn’t help that I was brought up in a traditional Pilipino household where I could only speak when spoken to, and where young women were groomed at an early age to just sit and look pretty.” As she began distributing her work to other Asian women, her drive to create zines took on a life of its own. “One day I just started cutting and pasting and writing on my computer and Bamboo Girl issue number one was pushed out of the oven. It turned out to be one of the most cathartic things I’ve ever done, and I haven’t stopped publishing it since.”

Although the Riot Grrrl movement declined in the mid ‘90s with corporate misappropriation of the slogan “Girl Power”, the zine movement is experiencing an impressive resurgence amongst young creative and militant women of color in an age of political repression, misogyny, and queerphobia. Babely Shades, a QTPOC art collective in Ottawa, Canada, fighting for radical inclusion, released their first zine, Babely Shades: Volume 1 Feelin’ Myself, centered on self-love, respect and whose cover featured mirror images of Nicki Minaj in 2016 as an ode to Black sisterhood. The group also released another zine entitled Black Punk. Women.Weed.Wifi, a marijuana collaborative in Seattle, released their third issue of Once Upon A Lit Time, a zine series dedicated to confessions of female friendship and life-changing times. In Britain, a collective called gal-dem released a zine as an answer to lack of representation in the United Kingdom. On the West Coast, the Long Beach Zine Fest celebrates its third year in 2017, featuring more than 100 zine creators, which include a plethora of women of color committed to telling their stories. While technology booms, the craftsmanship of zines is still very much alive for marginalized women as artistic expression.

Monika Estrella Negra, a Black zinester from Milwaukee, and the founder of the Black and Brown Punk Collective in Chicago, remembers the magic of discovering zines. She enjoyed reading Osa Atoe's Zine Shotgun Seamstress, which is now discontinued, Race Riot by Mimi Thy Nyugen, and Slash ‘Em Up by Kyle Ozero, one zine that was created by a Black single mother who was involved in the punk scene. “I was always fascinated by the accessibility of zines. They were like books, but under your complete control. The content I wanted to put into my zines were things I could never find in the books I would check out from libraries. I wanted people to enter my world, see the world through my eyes.”

Her first zine, entitled, Girl, Please, is her favorite zine. “That was about Pat Parker, and it addresses the issues I encountered when I started going to university, and was experiencing anti-blackness on extreme levels. It's called Girl Please and it has that infamous picture of the young black girl throwing shade at Hillary Clinton. Pat Parker was a radical black lesbian who made a poem called 'to the white person who wishes to be my friend'. And it's basically addressing the subconscious racism 'well meaning' white people espouse every day. That was a great chunk of my peers in school. 'Radical' white people who didn't even realize that they were just as racist as their parents that they hated.”

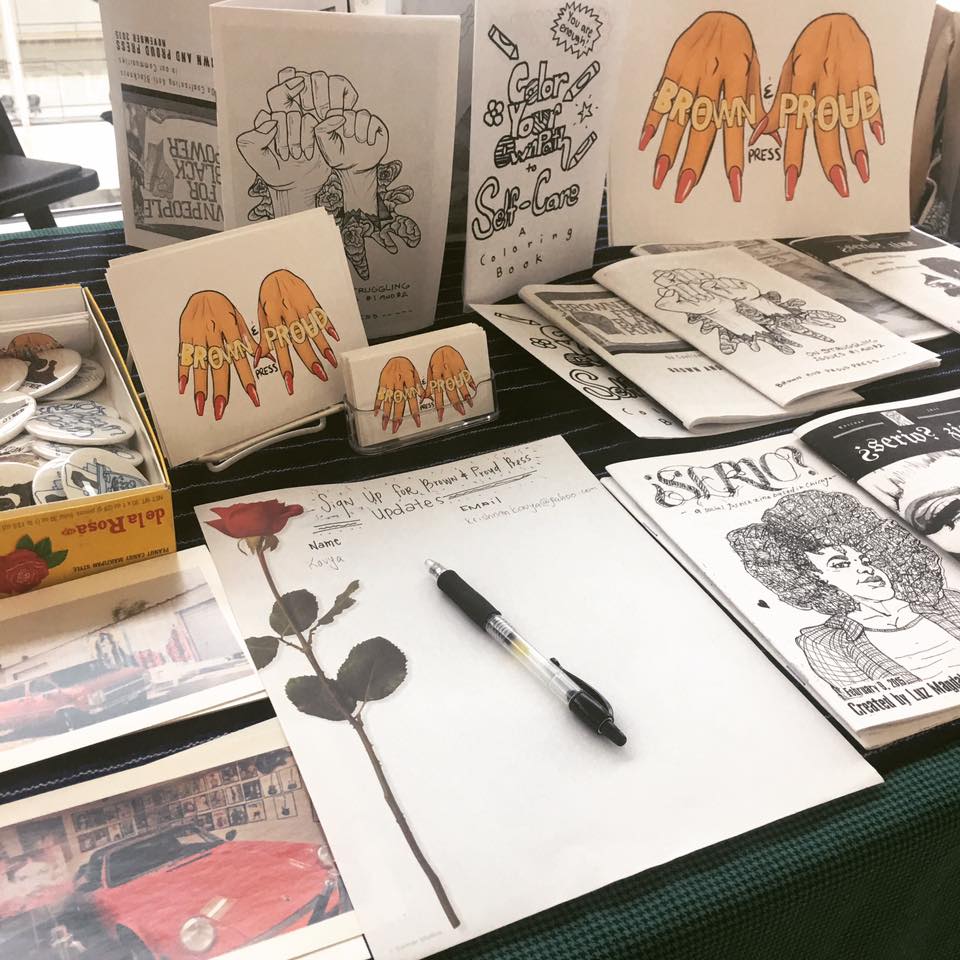

Luz Magdaleno, a member of Brown and Proud Press, a zine collective also based in Chicago, was also driven to zine-making for the autonomy it enabled. She became inspired to make zines in 2014 at a period of particularly intense political turmoil in the United States. “I was interested in documenting the stories of activists. Why they were so passionate and wanted to illuminate the work they were doing. This was in the midst of people climate march happening, Black Lives Matter movement and Ferguson bullshit. I was involved with Rise at Roosevelt University, a social justice activism group on campus. Didn’t feel like my photography and writing were being used as a tool for change, neither was my homie Alvaro Zavalas’s art [an illustrator] so we started our own zine. ¿SERIO? Zine highlighted a different topic each issue and invited a variety of activists to submit a piece on it. Issues we covered were environmental justice, women's rights, and Chicano identity.”

Estrella Negra and Luz represent millennials who are continuing to breathe life into a craft that many suggest is dying. With the death of the angry girl grunge movement in the ‘90s and the rise of technology, how will women of color continue to transform this underground art form? Will technology signal the end of zine culture, or merely aid in its metamorphosis in reaching more women of color? Here is where the two differ.

“Zines are the most radical form of resistance,”

- Luz Magdaleno

Above Image Source: 303 Magazine

Estrella Negra offers, “I think that the physical zine will eventually go out of style, and people will utilize blogs and their own webpages to talk about their perspectives. If anything, that's the best way to tap into your target audience, and also attract other folks you would never meet in person. Don't get me wrong, I love physical copies of zines. They are like books - the feeling of them can bring the best nostalgic feeling ever. Also the design element is pretty cool...I always used glue sticks and collages to create mine. That's what will be missed. It's also cheaper to put your work online, and hopefully, people will be able to charge for their words and intellect a higher degree than just selling a few zines.”

“Zines are the most radical form of resistance,” Magdaleno asserts. “All you need is a piece of paper and a pen and you can make a zine, fill it with information, art and resources! No relaying on technology or a white man! So zines will live forever. Technology has helped connect and share zines faster than ever before but it shouldn’t be deemed responsible for the success of zines-whatever that means.”

As internet culture shifts and the democratic nature of zine-making moves along with it, women of color will be here shaping the future of zine-culture as we know it, and we can’t wait to see what they do next.