FIGHT THE POWER

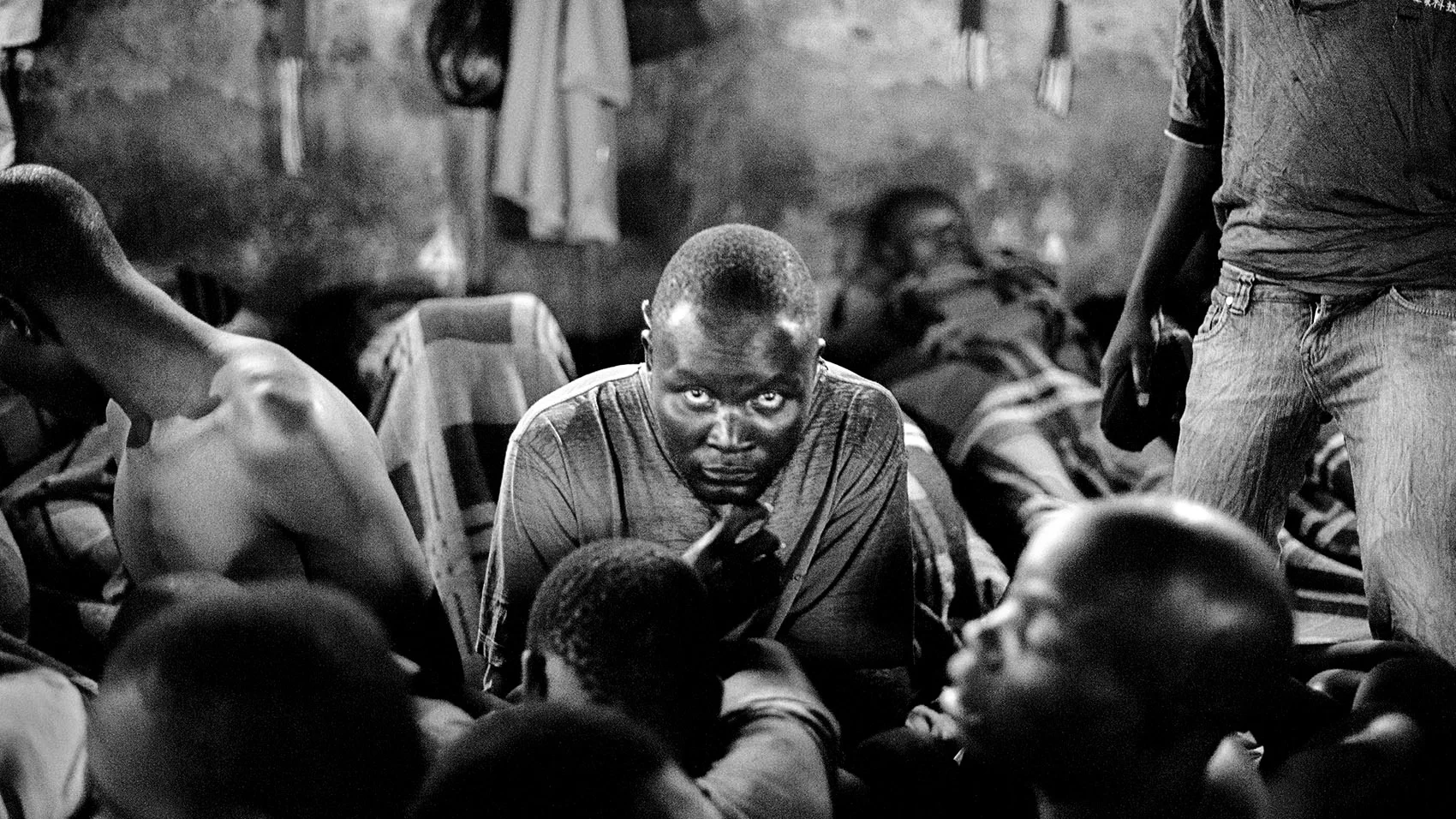

(Source: Above Photo Huffington Post)

Prisons Won’t End Violence Against Black Women: It’s Time For A Change

In 2014, Malcolm London, a co-chair for the Black Youth Project 100, was arrested by the Chicago Police Department at a protest, charged with aggravated assault. Within minutes, organizers, activists, and concerned observers tweeted and shared pictures of London, demanding his release from prison. Within an hour, the mood shifted significantly, as a young Black woman by the name of Kyra came forward, accusing the prominent organizer of sexual assault. The revelation sent shockwaves through the activist community, as it once again exposed the disturbing reality of the abuse of Black women within social justice movements. Sadly, violent mistreatment of Black women is, unfortunately, a story replayed all too often in political organizations. Black women, cisgender and trans, often remain silent about the physical and sexual abuse they experience at the hands of Black male leaders in order to maintain a united front and as a nod to respectability politics, without turning to the state, primarily prisons, for retribution. The question of the abuse of Black women leads to the question if men within the Black community frequently commit violence towards Black women, as well as the state that claims to protect us from violence, where can we turn to for retribution?

The prison abolition movement, which has gained considerable traction within the past 20 years, lists prisons as obsolete in constructively handling social problems; instead, prisons only serve to warehouse poor working class Black and Brown people who are targeted by the police and court systems. While race and class are discussed as central points in rejecting prisons to solve wrongdoings, gender particularly has yet to catch-up. In the case of sexual assault, the prison system proves to be inadequate in being an answer to ending rape culture, particularly when it affects Black women, both cis and trans.

Sexual assault is disturbingly commonplace in the prison system. Older Black women, as well as young teenage girls who enter juvenile courts, are frequently victims of assault in which the perpetrator is rarely held accountable. Teenagers, in particular, are more likely to fall into the youth incarceration after being sexually assaulted at a young age, as 60% of Black women are likely to be sexually assaulted before they turn 18. Black transgender women are also at a high risk of sexual abuse in prisons, jails, and juvenile detention centers. Black cisgender women are incarcerated at 4 times the rate of white women, while 1 in 2 Black trans women are incarcerated or have been incarcerated.

Black women who defend themselves from attacks are more likely to face punishment for it than their perpetrators. CeCe McDonald, a Black transgender woman who was verbally and physically attacked outside a bar by a white couple, faced a possible 20-year term for defending herself from the attack. 15-year-old Breasha Meadows was charged with aggravated murder after she was forced to kill her brutally abusive father in defense of the rest of her immediate family. In Florida, 2012, Marissa Alexander was prosecuted for aggravated assault with a lethal weapon after firing a warning shot at her abusive husband. If the state punishes Black women who defend themselves from transphobic, misogynistic, and racist violence by seeking to incarcerate them, how can the community seek retribution in that very same system?

“Black women who defend themselves from attacks are more likely to

face punishment for it

than their perpetrators.”

Part of prison abolition is not simply tearing down oppressive systems, but transforming society so that accountability for crimes is dealt with in a new way, one that particularly involves victims of the crime to actively take part in interventions with their community. Mariama Kaba, a respected and prominent Black female organizer agrees, in her in 2013 piece on ending rape culture. “I am actually in favor of trials or community accountability circles when someone is raped. Questions about what happened, how it happened, who was harmed (including friends, family & other community members), and how we can repair the harm caused deserve to be aired in public (or private). This is a good thing. As a survivor of sexual assault, I want rape to be discussed publicly. I want the names of rapists to be known. I want rape to end,” she argues. “I do not believe, however, in locking people up in prisons as punishment. There are many reasons for this and I will suggest four: 1. Prisons are not rehabilitative; 2. Prisons make people worse; 3. Prisons are not a deterrent to violence; 4. And most importantly for me as an anti-violence organizer, sentencing someone to prison likely condemns that individual to judicial rape.”

The future of ending gendered violence towards Black women cannot be done within the prison system; in order for justice to be obtained, we must take the reign in leading a movement to create abolition that understands that carceral feminism is not the answer to the intersections of gender and racial violence. “Despite the fact that women and LGBT people are frequent targets of the criminal-justice system, WGSS scholars in conjunction with mainstream feminist and LGBT movements have often turned to that same system as a remedy to various forms of gendered and sexualized violence,” writes Priya Kandaswamy. “From domestic violence to sexual assault to hate crimes, criminalization has emerged as a key strategy in mainstream struggles against violence, and, in many ways, the increased visibility of feminism, LGBT identities, and WGSS is intimately connected to their articulation to hegemonic law-and-order politics.”

In this current political climate, the prison is the antithesis towards ending the plight of racist, sexual violence towards Black women. Only by embracing abolitionist politics in which Black women lead can there be transforming politics that make us feel safe, valued, and free in our communities and the world at large.